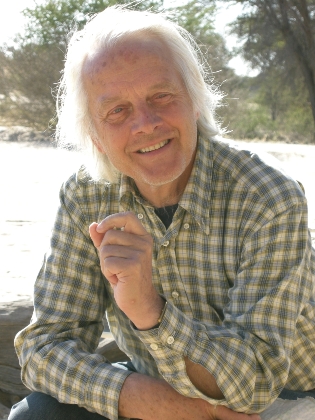

Interview: Hugh Brody

Hugh Brody’s latest film The Meaning of Life takes us around Kwikwexwelhp, a Canadian prison run by the Chehalis First Nation. He talks to Kamila Kuc about the unique quality of Kwikwexwelhp and the experience of making the film

Kamila Kuc: The Meaning of Life is about Kwikwexwelhp – minimum security prison in Canada, run by the representatives of the Chehalis First Nation. The concept of rehabilitation is based around Aboriginal teachings and spirituality. Do you think a prison like this could exist in any other country?

Hugh Brody: The Meaning of Life is a film about a particular prison in a particular place, and the place is the territory of a Canadian First Nation. The spirituality and the rituals that inform what goes on in the prison come from a particular tradition. It is also a particular moment in the history of that place: a time when Canadian authorities are in despair about the numbers of prisoners from indigenous backgrounds and the seemingly hopeless recidivism rates of all prisoners. Yet the stories that lie behind and within the film are stories that are being told in just about every country. Prisons are full of the marginal, the people who have been abused at home and in their societies, the poor, the racially or ethnically despised. These are the people who find themselves in prisons. And they are the people who have often been denied basic rights and simple respect, and in prisons where there are few if any rehabilitation programmes that are matched to who they are or who they want to be.

So there could – and probably should – be prisons like Kwikwexwelhp in Australia, New Zealand or any other nation where an indigenous population has been displaced and forced to the margins of a colonial world; and where there is an indigenous heritage that can be drawn on to provide ideas and help within the prisons. As well as the obvious ones, here are many nations that come to mind: the countries of Scandinavia, the USA and, of course, many if not all the countries of Central and South America.

There is more to be said here, though. The Meaning of Life is also a film about the possibility of redemption, and how this needs to be built into notions about what prison is for, and how rehabilitation can have some hope of success. And this means that there could be a profound and perhaps urgent need for prisons like Kwikwexwelhp in every part of the world.

KK: What is the financial situation of Kwikwexwelhp like? How is it funded?

HB: The prison is funded from the Canadian federal government, through Correctional Service Canada. There are those in the Service who worry about the cost per prisoner, which is higher than in larger institutions.

KK: The unique thing about the film is the fact that we see the prison life from the inmates’ point of view. The camera follows them in their everyday activities and we listen to their, often tragic, life stories. How long did it take you to gain their trust and complete the whole film?

HB: I spent about two years in the prison and hundreds of hours talking with prisoners. Some of the men were quick to welcome the process, and were open in filmed interviews within a few days of knowing them. Others were much more wary and, in one important case, only began to trust us after more than a year. As with all such film making, trust was complex in the way it unfolded. Some of the men whom I knew best went from interest to a quite deep involvement – these are men, after all, with nothing but time on their hands and a strong need to be heard, especially by people from outside the prison system. In most cases, I did many interviews with the same people, speaking to them over and over again, not always but periodically on camera.

The trust built from interview to interview. There was also a more general kind of trust within the prison as a whole, which was crucial for the work. The men as a whole, along with the administration and staff, had to have some kind of basic confidence in who we were and what we were doing. I worked all the time with the same cameraman, Kirk Tougas (whom I had done other films with and who is very respectful and considerate in the way he works); and, for two shooting periods, I had my son Tomo working with us as sound assistant and second camera. The men seemed to be especially delighted to meet Tomo and some took obvious interest in talking to someone in his twenties. So the nature of the team helped build and secure trust.

KK: Can you recall any challenging moments during the shootings?

HB: There were problems of trust with some of the guards in the prison, and some difficult moments when it came to dealing with occasional challenges to our freedom to move around inside the prison or be alone with prisoners in their rooms. But this was in many ways a surprisingly easy film to shoot, with very strong support from just about everyone in the prison. Those who did not want to be involved, or who were friendly but did not want to be on camera, made this clear very early on in the work and seemed quite happy for the filming to go on around them.

KK: The film raises the question of the purpose for the existence of traditional prisons. Kwikwexwelhp, as Rita Leon, the Grandma and Elderly Chechalis points out, is about healing rather than punishment. It is a place where redemption is possible through spiritual approach and teaching. Did you feel that Kwikwexwelhp was a special place?

HB: I have said something about redemption in my answer to your first question. But more on this can be said quite simply: I had the sense throughout the filming that Kwikwexwelhp was an extraordinary place for many (though not all) of the inmates because it really did offer respect and a sense of the possibility of redemption that came from the attitudes and spiritual teachings of Chehalis. I suppose I did at times feel disappointment about the way Correctional Service Canada gave qualified and faltering support to the concept, and the way changes in key personnel resulted in a fall-off in commitment to the ideals.

KK: What were your first observations? What impressed and disappointed you the most about the place? Something that has surprised you perhaps?

HB: My first observations and the surprises? I was astonished by many of the inmates – by the stories they told, the extremes they had lived through both in childhood, in the crimes they had committed and then in prisons, and yet was again and again surprised also by their warmth and thoughtfulness. These were evident just about from the first hours I spent with the men.

Then there was Grandma Rita Leon – a woman of such astounding and gentle and seemingly simple wisdom. She surprised me at our first meeting, and went on surprising me throughout the project. Her own story is, sadly, not in the film; but her huge presence is, I think.

KK: Looking at all inmates at the beginning of the film, we can hardly imagine them committing any of these atrocious crimes. The Grandma explains that their wrongdoings are down to their past and things that had happened to them, thus we should not be judgmental. A thought that comes to mind is that it is society that creates criminals and equally, it is society that should offer them a chance to redeem themselves. What are your views on the whole issue and on Kwikwexwelhp itself?

HB: I got to know the life stories of nineteen prisoners. Most had committed terrible crimes; over half of them were in for murder, and some for horrific sexual offences. All but three of them had suffered extremes of abuse or violence as small children, and were caught in spirals of crime and incarceration from their teenage years. Most of the inmates from First Nations communities had been in residential schools for just about all their childhood, where they had been sexually abused as well as immiserated in just about every way. Hearing these stories it was impossible not to see the links between their crimes and the social institutions they had lived in; and, indeed, have a sense of the inevitability of their crimes.

And of course the society that set the stage for these lives, and shaped the grim inevitabilities, has to own up to its role and seek to manage and deal with the consequences. Societies have to redeem themselves. Yet many of the crimes are terrible and some of the criminals are not going to seek or find any kind of redemption. So prisons have a profoundly difficult, perhaps contradictory, task: to confine and punish while also looking for rehabilitation. The puzzle, and a kind of agony, in this is that prison is itself an inherently abusive institution; so how is it going to be able to build the possibility of redemption? I suppose Kwikwexwelhp is fascinating and moving and important because it may be a way out of the contradiction. But it is still a prison.

KK: How did they feel being filmed and what was their reaction to the final product?

HB: Just about all the men in the film said that they very much liked being interviewed and being filmed. I like to think that this was because of the way we approached the work and the manner of the filming. We gave the men a lot of time and listened to what they had to say. They also were proud of the work they did, be it making a garden, tying fishing, baking bread or carving masks. So far, those who have seen the film have expressed huge appreciation for it.

There are still screenings to be scheduled in some of the prisons or halfway houses where men now are, and there could be other reactions to come. But the comments after screenings in prisons by men in the film as well as inmates not in the film have again and again referred to the absence of any outside commentary as something they particularly liked. They see the film as theirs, however much they know it is 82 minutes edited from about 90 hours of footage.

KK: Kwikwexwelhp is about cultivating Aboriginal tradition. How does the Canadian Government feel about this? We all know the US policies towards the Native Americans…

HB: Since the late 1960s, Canadian governments have on the whole been supportive of Aboriginal cultural traditions. They have not been so supportive of claims to land and resources, but heritage, including ideas about spirituality and indigenous ritual, has been supported by many government programmes and even by the churches.

KK: In 1991 you made The Immemorial, about the Nishaga’s people and then in 1994 there was The Washing of Tears about the Mowachaht people. The Meaning of Life came 14 years later…Why such a long break in filmmaking?

HB: The break has not been quite that long. I made Inside Australia in 2003, and also have been filming off and on in the southern Kalahari in South Africa over the last twelve years (this footage now in post-production). So I have managed to keep working on films despite the problems so many of us have had with getting commissions or funding from broadcasters.

KK: I have read some information about the choice of title for the film and I particularly like the reference to Monty Python but perhaps you can tell LIDF readers a little more about finding the meaning of life…

HB: As you might imagine, the title began as a joke. From the first stages of work on the project I labeled my files “The Meaning of Life” as a sort of teasing of myself. Then as the film got to the fine cut stage, after over a year of intensive and quite difficult editing (with the very brilliant Haida Paul), the question of title had to be resolved. Something about the scale and breadth and, I believe, depth of the material as well as the kind of issues being raised, meant that the title The Meaning of Life seemed to make sense. Despite the possible hubris and the joke, maybe with the help of it, none of us who had been working on the film could think of anything that seemed better.